PostgreSQL (often simply “Postgres”) has earned its reputation as the “most advanced open-source relational database” not just through features, but through a robust, battle-tested architecture. Understanding how Postgres works under the hood is crucial for DBAs, backend engineers, and anyone looking to optimize performance or troubleshoot complex issues.

In this guide, we will dissect the PostgreSQL architecture, exploring how its memory, processes, and storage subsystems work together to ensure data integrity and high performance.

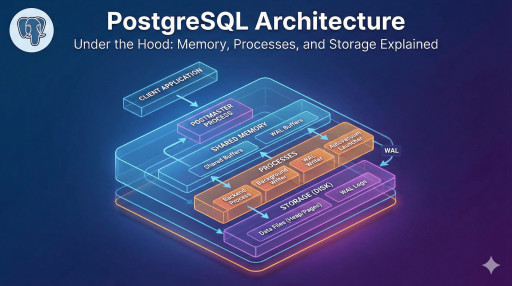

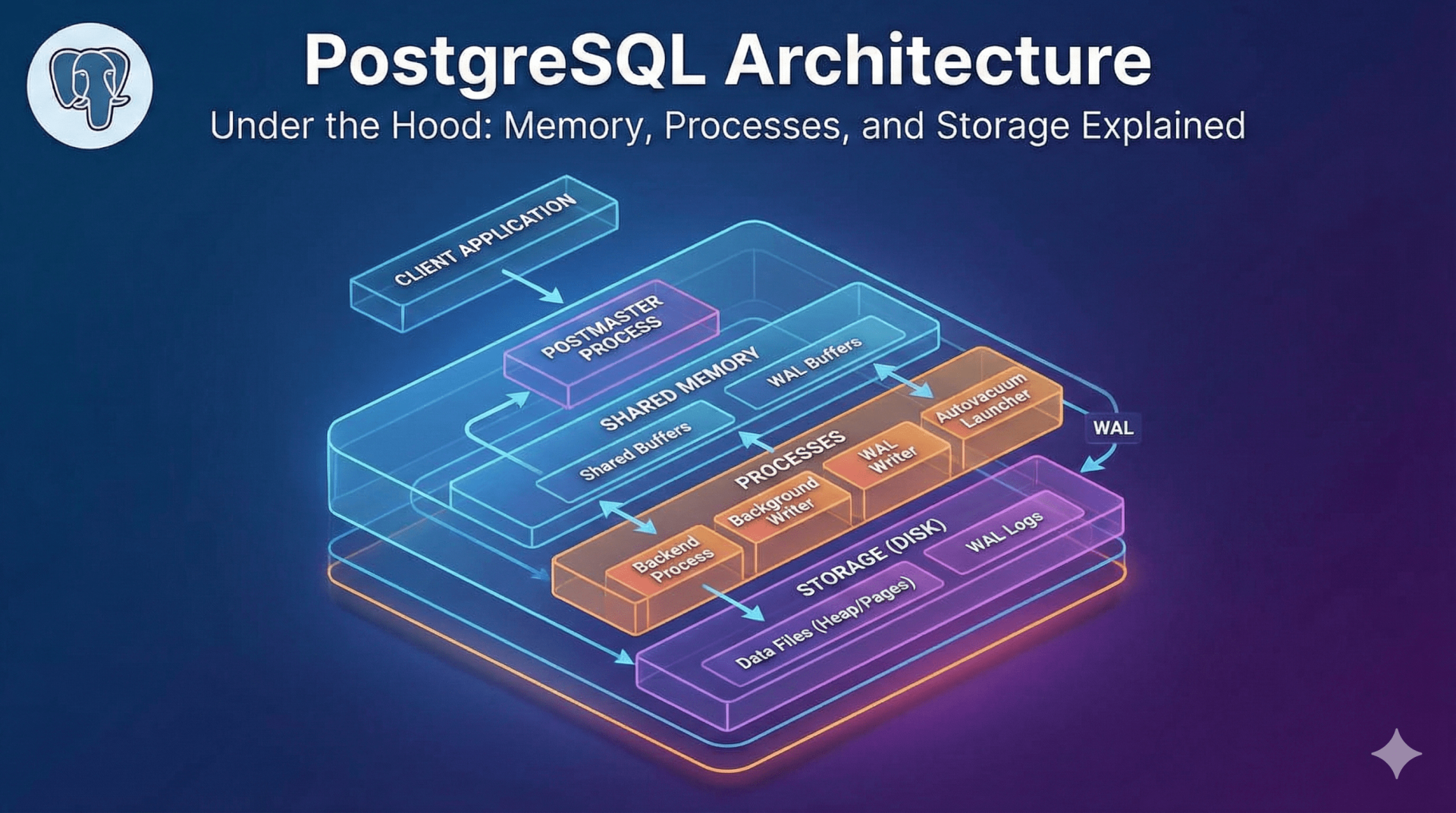

1. High-Level Overview: The Client-Server Model

At its core, PostgreSQL follows a classic process-based client-server model. Unlike threaded databases (like MySQL’s InnoDB), Postgres manages concurrency through separate processes.

The system consists of two main sides:

- The Client: An application (web server, psql CLI, JDBC driver) that sends a request.

- The Server: The

postgresexecutable that manages the database files, accepts connections, and performs actions on behalf of the client.

When a client connects, the main server process (often called the Postmaster) forks a new, dedicated process for that specific connection. This ensures isolation; if one client process crashes, it rarely takes down the whole server.

2. Process Architecture

The executable setup of PostgreSQL is a collection of cooperating processes. These can be categorized into three groups:

A. The Postmaster (Main Process)

This is the supervisor. It starts up the system, shuts it down, and listens for incoming connection requests. When a request arrives, it spins up a Backend Process.

B. Backend Processes

These are the “workers.” Every connected user gets their own backend process (serviced by the postgres executable). It handles query parsing, execution, and returns results to the client.

C. Background Utility Processes

These processes run independently of client connections to keep the database healthy. Key processes include:

- Background Writer: Moves “dirty” (modified) pages from memory to disk to prevent data loss.

- Checkpointer: Ensures consistency by flushing data to data files and updating the Write-Ahead Log (WAL).

- Autovacuum Launcher: Automates the cleanup of dead rows (bloat) left behind by updates or deletes.

- WAL Writer: Periodically writes the WAL buffer to permanent storage.

3. Memory Architecture

Understanding how Postgres uses memory is critical for tuning postgresql.conf. The memory is divided into two distinct areas: Local Memory and Shared Memory.

Shared Memory (Global)

This area is accessible by all processes of the PostgreSQL server.

- Shared Buffers: The most critical component. It caches data blocks read from the disk. When a process needs data, it looks here first. If it’s not found, it pulls from the OS cache or disk.

- WAL Buffers: A temporary holding area for transaction logs before they are written to disk. This ensures write performance is fast, as writing to memory is quicker than seeking on a disk.

Local Memory (Per-Process)

Each backend process requires its own memory to execute queries.

work_mem: Used for sorting operations (ORDER BY) and hash tables (joins). If a query requires more than the allocatedwork_mem, Postgres spills data to temp files on the disk, drastically slowing down performance.maintenance_work_mem: Used for maintenance tasks likeVACUUM,CREATE INDEX, andALTER TABLE.

Pro Tip: Don’t set

work_memtoo high globally. Since it is allocated per operation within a query, 100 concurrent connections doing complex sorts can easily consume all your RAM, leading to Out-Of-Memory (OOM) kills.

4. Storage and The File System

Postgres stores data in files, but it doesn’t write to them randomly. It organizes data into specific structures.

The Heap and Pages

Data is stored in files composed of fixed-size units called Pages (or Blocks), usually 8 kB in size.

- The Heap: This is where the actual table rows (tuples) live.

- Tuples: The row data itself.

- Item Pointer: An identifier used by indexes to find the specific physical location of a row in the heap.

5. The “Secret Sauce”: MVCC and WAL

Two mechanisms define Postgres’ reliability and concurrency capabilities.

MVCC (Multi-Version Concurrency Control)

Postgres solves the problem of multiple users reading and writing data simultaneously without locking the entire database.

- How it works: When you update a row, Postgres doesn’t overwrite the old data. Instead, it creates a new version of the row and marks the old one as “obsolete” (dead).

- The Result: “Readers don’t block writers, and writers don’t block readers.” A user running a long report sees a snapshot of the database as it was when the query started, even if other users are updating those records.

WAL (Write-Ahead Logging)

To ensure data integrity (ACID compliance), Postgres uses WAL.

Log Change -> Commit -> Write Data to Disk Later

Before any change is made to the data files, it is written to the WAL. If the server crashes (power loss), Postgres can “replay” the WAL to restore the database to a consistent state.

6. The Life of a Query

What happens when you run SELECT * FROM users?

- Parser: Checks the SQL syntax and creates a “parse tree.”

- Rewriter: Applies rules (like Views) to rewrite the query into its final form.

- Planner/Optimizer: The brain of the operation. It analyzes statistics to determine the fastest path (Scan type, Join method, Index usage). It calculates the “cost” of different paths.

- Cost = (Disk Reads * Seq Page Cost) + (CPU usage)

- Executor: Takes the plan and recursively calls functions to retrieve the rows, following the MVCC rules to ensure the user sees the correct data version.

Conclusion

The architecture of PostgreSQL is a balance of complex memory management, process isolation, and storage reliability. By understanding the distinction between Shared Buffers and OS Cache, or how MVCC generates “dead rows” that require Vacuuming, you move from being a database user to a database administrator.

Whether you are tuning work_mem for complex analytical queries or configuring max_connections for a high-traffic web app, keeping this architectural map in mind is your key to scaling PostgreSQL successfully.