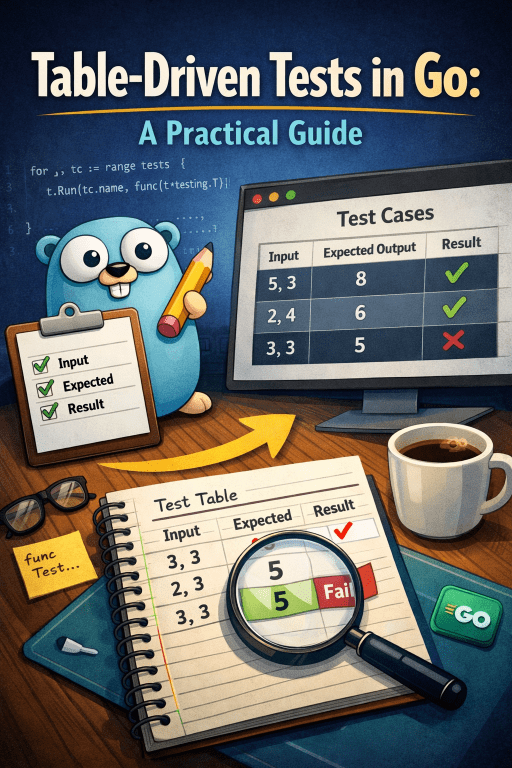

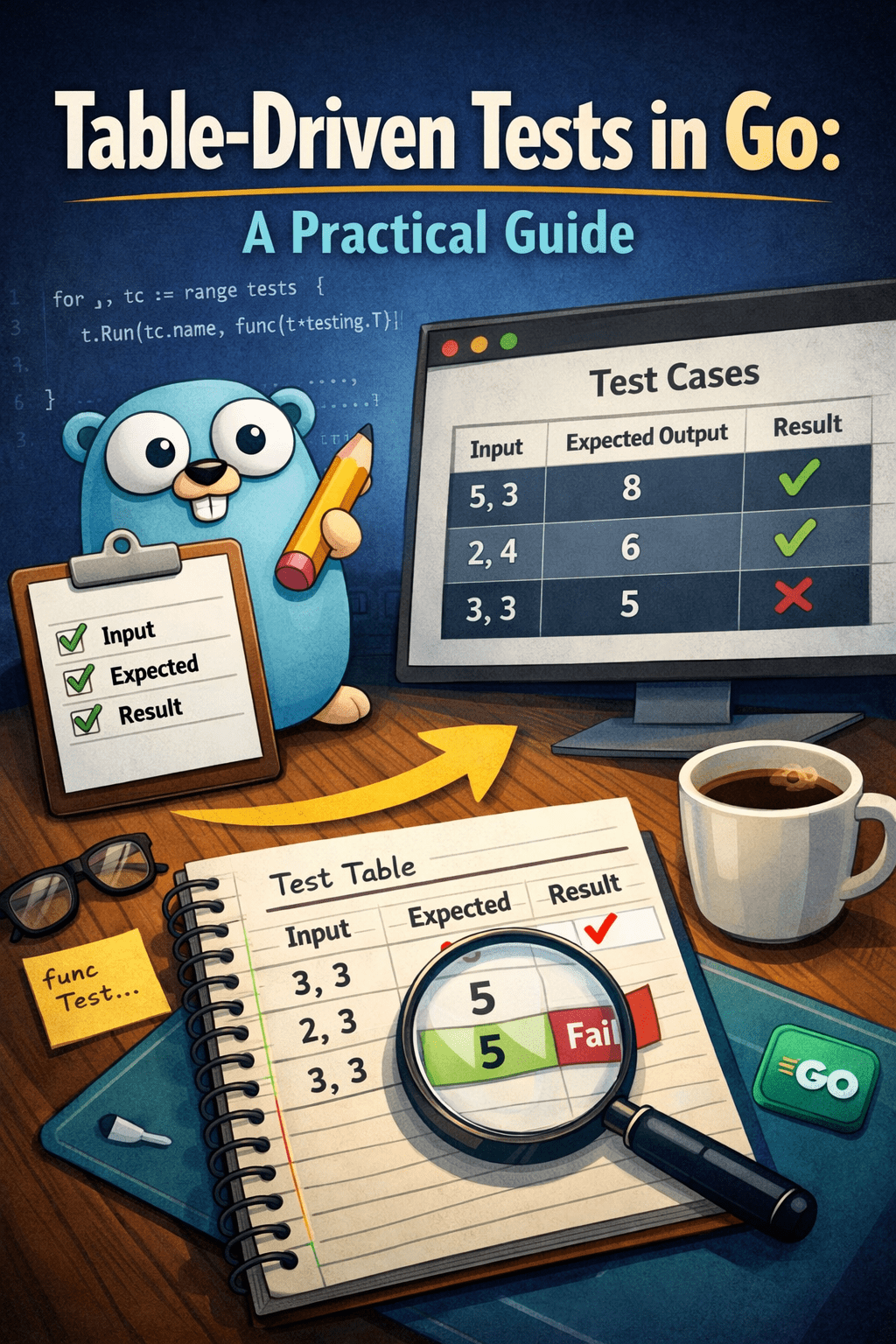

In the world of software development, writing robust and maintainable tests is crucial for ensuring code reliability. Go, with its built-in testing package, makes unit testing straightforward and efficient. One powerful technique that stands out for its elegance and scalability is table-driven testing. This approach allows you to define multiple test cases in a structured table format, making your tests easier to read, extend, and maintain.

Whether you’re a beginner dipping your toes into Go testing or an experienced developer looking to refine your practices, this guide will walk you through the ins and outs of table-driven tests. We’ll cover the basics, provide practical examples, and share tips to help you integrate this method into your workflow. By the end, you’ll have a solid understanding of how to leverage table-driven tests to write cleaner, more effective Go code.

Why Use Table-Driven Tests?

Before diving into the how-to, let’s discuss the why. Traditional tests in Go often involve writing separate functions or repetitive assertions for each scenario. This can lead to bloated test files, duplicated code, and difficulty in adding new cases.

Table-driven tests address these issues by centralizing test data into a slice of structs (the “table”). Each struct represents a test case with inputs and expected outputs. You then loop over this table, running assertions for each entry. This results in:

- Conciseness: Less boilerplate code.

- Readability: Test cases are easy to scan and understand at a glance.

- Extensibility: Adding a new test case is as simple as appending to the table.

- Consistency: Ensures all cases are tested uniformly.

Table-driven tests are particularly useful for functions with varied inputs, edge cases, or combinatorial logic, such as parsers, validators, or mathematical operations.

Getting Started with Go Testing Basics

If you’re new to Go testing, here’s a quick primer. Go’s standard library includes the testing package, which provides everything you need. Tests are written in files ending with _test.go and functions prefixed with Test.

A simple test looks like this:

package mypackage

import "testing"

func Add(a, b int) int {

return a + b

}

func TestAdd(t *testing.T) {

result := Add(2, 3)

if result != 5 {

t.Errorf("Add(2, 3) = %d; want 5", result)

}

}To run tests, use go test in your terminal. This executes all test functions and reports failures.

Now, imagine testing Add with multiple pairs: (1,1), (0,0), (-1,1), etc. Repeating the assertion block for each would be tedious. Enter table-driven tests.

Implementing Table-Driven Tests: A Step-by-Step Example

Let’s convert the above into a table-driven test. The key steps are:

- Define a struct to hold test case data (inputs and expected output).

- Create a slice of these structs.

- Loop over the slice in your test function.

- For each case, call the function under test and assert the result.

Here’s the implementation for our Add function:

package mypackage

import "testing"

func TestAdd(t *testing.T) {

tests := []struct {

a, b int

want int

}{

{1, 1, 2},

{2, 3, 5},

{0, 0, 0},

{-1, 1, 0},

{100, -50, 50},

}

for _, tt := range tests {

got := Add(tt.a, tt.b)

if got != tt.want {

t.Errorf("Add(%d, %d) = %d; want %d", tt.a, tt.b, got, tt.want)

}

}

}Notice how the anonymous struct uses field names like a, b, and want for clarity. The loop uses range to iterate, and t.Errorf provides detailed failure messages.

This structure scales beautifully. Need to test for overflow or other edge cases? Just add more entries to the tests slice.

A More Complex Example: String Reversal

Let’s apply this to a function that reverses a string, handling various cases like empty strings, Unicode, and special characters.

First, the function:

package mypackage

func Reverse(s string) string {

runes := []rune(s)

for i, j := 0, len(runes)-1; i < j; i, j = i+1, j-1 {

runes[i], runes[j] = runes[j], runes[i]

}

return string(runes)

}Now, the table-driven test:

package mypackage

import "testing"

func TestReverse(t *testing.T) {

tests := []struct {

input string

want string

}{

{"hello", "olleh"},

{"", ""},

{"a", "a"},

{"ab", "ba"},

{"Go is awesome!", "!emosewa si oG"},

{"こんにちは", "はちにんこ"}, // Handles Unicode

{"12345", "54321"},

{"special chars: !@#", "#@! :srahc laiceps"},

}

for _, tt := range tests {

got := Reverse(tt.input)

if got != tt.want {

t.Errorf("Reverse(%q) = %q; want %q", tt.input, got, tt.want)

}

}

}This example demonstrates how table-driven tests handle diverse inputs seamlessly. The %q format in t.Errorf ensures strings are printed with quotes for better debugging.

Using Subtests for Better Organization

For larger test suites, Go’s t.Run allows subtests, which can name each table entry for targeted running (e.g., go test -run TestReverse/empty).

Enhance the Reverse test like so:

func TestReverse(t *testing.T) {

tests := []struct {

name string

input string

want string

}{

{"simple", "hello", "olleh"},

{"empty", "", ""},

{"single char", "a", "a"},

{"unicode", "こんにちは", "はちにんこ"},

// ... other cases

}

for _, tt := range tests {

t.Run(tt.name, func(t *testing.T) {

got := Reverse(tt.input)

if got != tt.want {

t.Errorf("Reverse(%q) = %q; want %q", tt.input, got, tt.want)

}

})

}

}Adding a name field to the struct makes tests more descriptive and easier to isolate during debugging.

Handling Errors and Complex Assertions

Table-driven tests aren’t limited to simple equality checks. For functions that return errors, include an error field in your struct.

Consider a function that parses an integer from a string:

package mypackage

import (

"errors"

"strconv"

)

func ParseInt(s string) (int, error) {

if s == "" {

return 0, errors.New("empty string")

}

return strconv.Atoi(s)

}The test:

func TestParseInt(t *testing.T) {

tests := []struct {

input string

want int

wantErr bool

}{

{"123", 123, false},

{"-456", -456, false},

{"abc", 0, true},

{"", 0, true},

}

for _, tt := range tests {

got, err := ParseInt(tt.input)

if (err != nil) != tt.wantErr {

t.Errorf("ParseInt(%q) error = %v; wantErr %v", tt.input, err, tt.wantErr)

continue

}

if got != tt.want {

t.Errorf("ParseInt(%q) = %d; want %d", tt.input, got, tt.want)

}

}

}Here, we check for errors first and skip further assertions if an error was unexpected (using continue).

For more complex assertions, you can use libraries like github.com/google/go-cmp/cmp for deep equality on structs or slices.

Best Practices for Table-Driven Tests

To get the most out of this technique:

- Keep Tables Focused: Limit each test function to related cases. Split into multiple functions if the table grows too large.

- Use Descriptive Names: Field names like input, expected, or wantErr improve readability.

- Handle Panics: Use t.Cleanup or recover in subtests for functions that might panic.

- Parallelize When Possible: Add t.Parallel() in subtests for faster execution, but ensure thread-safety.

- Avoid Overuse: Not every test needs to be table-driven. Simple one-off tests are fine as is.

- Test Edge Cases: Always include boundaries like nil, zero, max values, and invalid inputs.

- Integrate with CI/CD: Ensure your tests run in automated pipelines for consistent validation.

One potential downside is that a failure in one case doesn’t stop the loop, so you might get multiple error messages. However, this is often helpful for identifying patterns in failures.

Conclusion

Table-driven tests are a cornerstone of effective Go testing, promoting clean code and comprehensive coverage. By structuring your test data in tables, you reduce duplication and make maintenance a breeze. Start small with a basic function, then apply it to more complex scenarios in your projects.

If you’re building a Go application, experiment with this pattern in your next test suite.