Rust is renowned for its focus on safety, performance, and concurrency. One of its most powerful yet initially perplexing features is lifetimes. If you’re coming from languages like C++ or even higher-level ones like Python, lifetimes might seem like an unnecessary complication. But once you grasp them, they become a superpower that prevents entire classes of bugs at compile time. In this in-depth guide, we’ll dive deep into Rust lifetimes, exploring their purpose, syntax, and practical applications. Whether you’re a beginner rustacean or an experienced developer looking to refine your understanding, this article will equip you with the knowledge to wield lifetimes effectively.

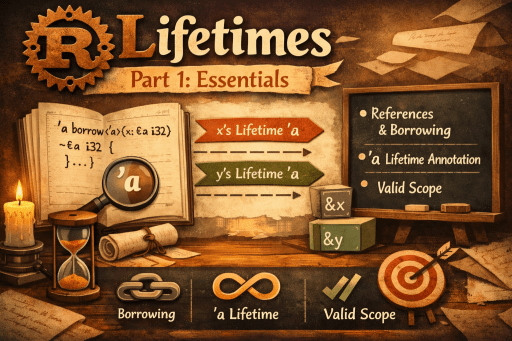

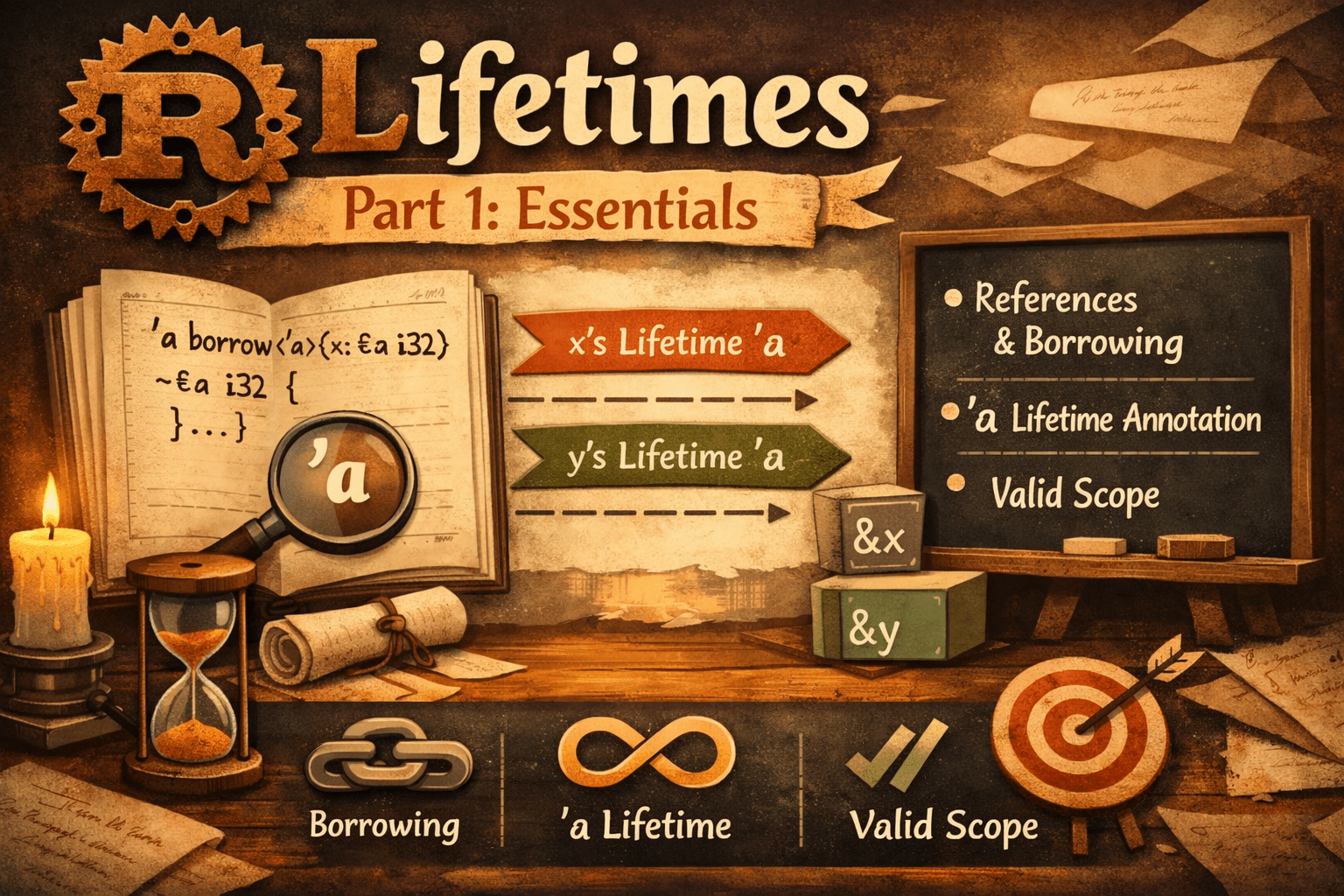

This is Part 1 of the series. We’ll cover the introduction, table of contents (index), and the foundational concepts. Future parts will delve into more advanced topics, code examples, and troubleshooting.

Introduction to Rust Lifetimes

In Rust, memory safety is enforced without a garbage collector through the ownership system, which includes borrowing and references. However, references can sometimes outlive the data they point to, leading to dangling pointers—a classic source of bugs in systems programming. Enter lifetimes: a compile-time mechanism that tracks how long references are valid.

Lifetimes aren’t about how long something lives in memory (that’s handled by scopes and drop semantics). Instead, they’re annotations that tell the compiler the relationships between the lifetimes of references. This ensures that you can’t use a reference after its referent has been dropped.

Why does this matter? Rust’s borrow checker uses lifetimes to validate code statically. Without explicit lifetimes in certain cases, the compiler might reject safe code or allow unsafe code. Mastering lifetimes allows you to write flexible, generic code—especially in functions, structs, and traits—while maintaining Rust’s zero-cost abstractions.

Consider a simple analogy: Imagine borrowing a book from a library. The “lifetime” is the period you can read it before returning it. If you try to read it after the due date, that’s invalid. Rust’s lifetimes enforce this rule at compile time.

By the end of this guide, you’ll understand how to annotate lifetimes, apply elision rules, and debug common errors. Let’s get started!

Index (Table of Contents)

Here’s an overview of the full article series for easy navigation:

- Introduction to Rust Lifetimes (Covered in Part 1)

- Why Lifetimes Are Needed: The Problem of Dangling References (Covered in Part 1)

- Basic Syntax of Lifetime Annotations (Covered in Part 1)

- Lifetimes in Functions (Part 2)

- Lifetimes in Structs and Enums (Part 2)

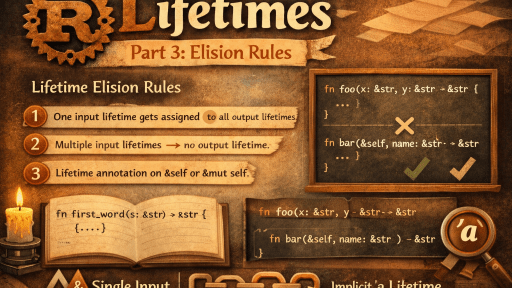

- Lifetime Elision Rules: When You Can Skip Annotations (Part 3)

- The ‘static Lifetime: Eternal References (Part 3)

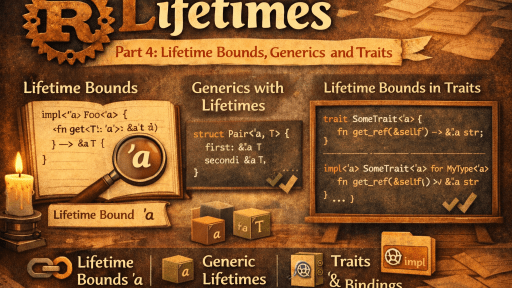

- Advanced Topics: Lifetime Bounds, Generics, and Traits (Part 4)

- Common Lifetime Errors and How to Fix Them (Part 4)

- Real-World Examples and Best Practices (Part 5)

- Conclusion and Further Resources (Part 5)

Each section includes code examples, explanations, and tips to reinforce the concepts.

Why Lifetimes Are Needed: The Problem of Dangling References

To appreciate lifetimes, we need to understand the problem they solve. In Rust, every value has an owner, and references (&) allow borrowing without transferring ownership. But what if a reference outlives its owner?

Here’s a classic example of a dangling reference issue that Rust prevents:

fn main() {

let r; // r is declared here

{

let x = 5; // x is created in this inner scope

r = &x; // r borrows x

} // x is dropped here

println!("r: {}", r); // Error! Trying to use r after x is gone

}This code won’t compile. The borrow checker sees that x is dropped at the end of the inner scope, but r tries to use it afterward. The error message might look like:

error[E0597]: `x` does not live long enough

--> src/main.rs:5:13

|

5 | r = &x;

| ^ borrowed value does not live long enough

6 | }

| - `x` dropped here while still borrowed

7 |

8 | println!("r: {}", r);

| - borrow later used hereThis is Rust’s safety net in action. But in more complex scenarios—like functions returning references or structs holding refs—the compiler needs hints about lifetime relationships. That’s where explicit lifetime annotations come in.

Without lifetimes, generic code could be ambiguous. For instance, a function taking two references might return one, but which one’s lifetime does it follow? Lifetimes clarify this, ensuring the returned reference doesn’t outlive the shortest-lived input.

In essence, lifetimes bridge the gap between Rust’s strict ownership rules and the flexibility needed for real-world programming. They prevent use-after-free errors, data races, and other memory issues that plague languages like C.

Basic Syntax of Lifetime Annotations

Lifetimes are denoted by a tick (‘) followed by a name, like ‘a or ‘foo. By convention, we use short, lowercase letters like ‘a, ‘b. These are parameters, similar to generics (<T>), but for durations instead of types.

Lifetime annotations appear in function signatures, struct definitions, and more. Here’s the basic form for a function:

fn longest<'a>(x: &'a str, y: &'a str) -> &'a str {

if x.len() > y.len() {

x

} else {

y

}

}In this longest function:

- <‘a> declares a lifetime parameter.

- &’a str means the reference to str lives at least as long as ‘a.

- The return type &’a str ties the output’s lifetime to ‘a, meaning it won’t outlive the inputs.

Both inputs share the same ‘a, so the returned reference is valid as long as the shortest input lives. If you passed strings with different lifetimes, the compiler would enforce the intersection.

You can have multiple lifetimes:

fn example<'a, 'b>(x: &'a str, y: &'b str) -> &'a str {

x // Returns x, so tied to 'a

}Here, ‘a and ‘b are independent. The return follows ‘a.

In structs, lifetimes ensure fields with references are safe:

struct Book<'a> {

title: &'a str,

author: &'a str,

}The ‘a means both fields’ references must outlive the Book instance.

These basics form the foundation. In Part 2, we’ll explore how to use lifetimes in functions with more complex examples.

Stay tuned for Part 2, where we’ll dive into lifetimes in functions and structs, complete with hands-on code examples and breakdowns.