Welcome back to our in-depth series on Rust lifetimes! In Part 1, we covered the introduction, the table of contents, the rationale behind lifetimes, and their basic syntax. If you haven’t read it yet, I recommend starting there for a solid foundation.

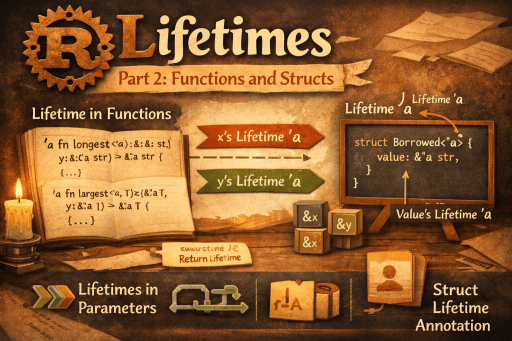

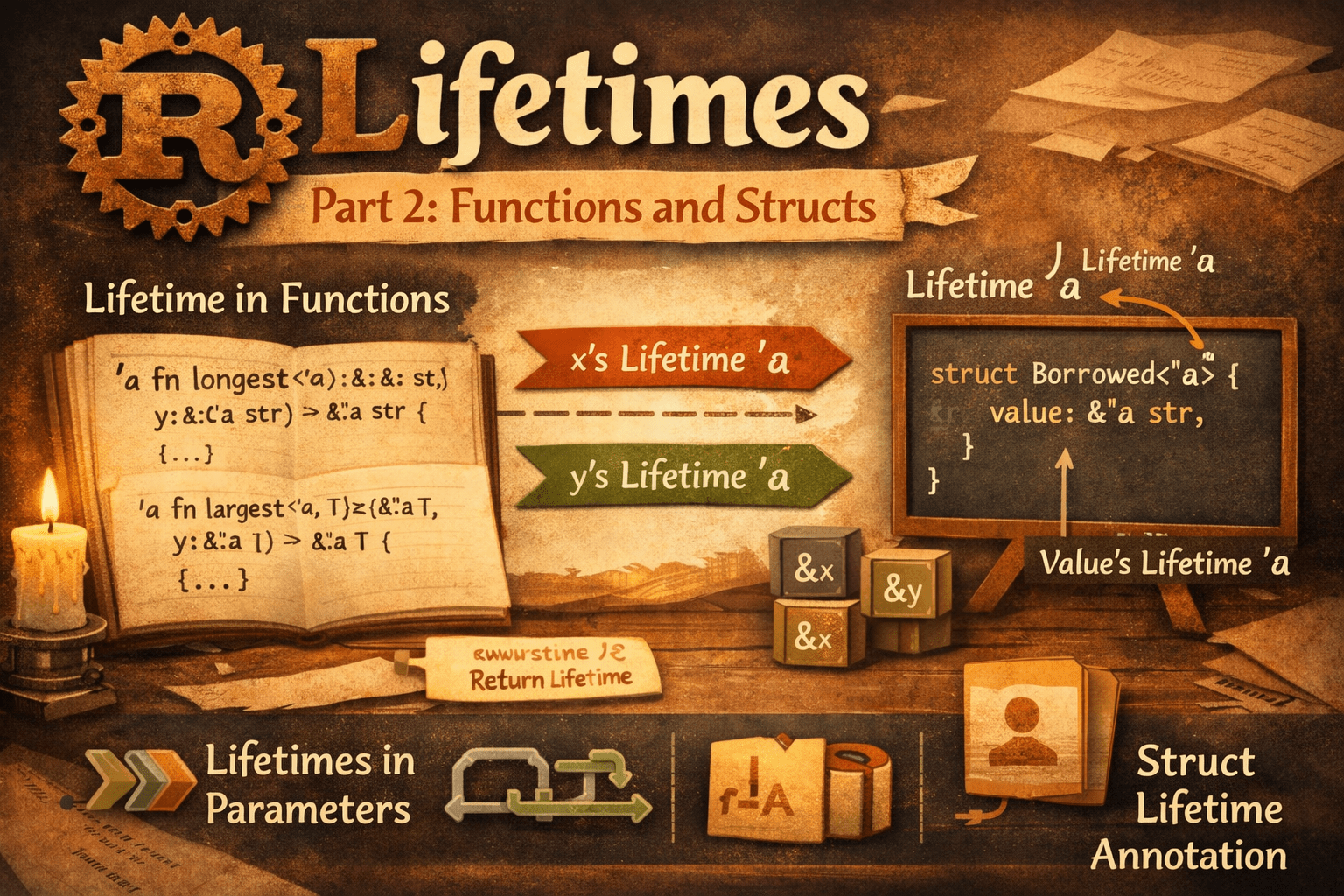

In Part 2, we’ll build on that by exploring how lifetimes apply in practical scenarios. Specifically, we’ll dive into lifetimes in functions and then in structs and enums. These are where lifetimes shine, enabling safe, reusable code without runtime overhead. We’ll include detailed code examples, explanations, and common pitfalls to watch out for.

Remember, lifetimes are all about ensuring references don’t dangle. Let’s jump in!

Lifetimes in Functions

Functions are a primary place where lifetimes come into play, especially when dealing with references as inputs or outputs. Without proper annotations, the borrow checker might conservatively reject your code, even if it’s safe.

The Role of Lifetimes in Function Signatures

When a function takes references and returns a reference, the compiler needs to know the relationship between the input lifetimes and the output. This prevents returning a reference that outlives its data.

Recall the longest example from Part 1:

fn longest<'a>(x: &'a str, y: &'a str) -> &'a str {

if x.len() > y.len() {

x

} else {

y

}

}Here, both parameters share ‘a, and the return type is also ‘a. This means the returned string slice is guaranteed to live as long as the shortest of x or y.

What if the lifetimes differ? You can use multiple lifetime parameters:

fn extract_first<'a, 'b>(x: &'a str, y: &'b str) -> &'a str {

x // Explicitly returning a ref tied to 'a

}In this case, the return lifetime is ‘a, independent of ‘b. Calling it might look like:

fn main() {

let string1 = String::from("long string");

let result;

{

let string2 = String::from("short");

result = extract_first(&string1, &string2);

}

println!("Result: {}", result); // This is fine, as result ties to string1's lifetime

}If you tried to return y instead (tied to ‘b), and ‘b was shorter, the compiler would complain if used beyond ‘b.

Generic Functions with Lifetimes

Lifetimes often pair with generics for flexible code. For example, a function that works with any type but handles references:

fn longest_with_announcement<'a, T>(x: &'a str, y: &'a str, ann: T) -> &'a str

where

T: std::fmt::Display,

{

println!("Announcement: {}", ann);

if x.len() > y.len() {

x

} else {

y

}

}Here, ‘a is for lifetimes, T for types. The where clause bounds T to Display for printing.

Usage:

fn main() {

let s1 = "hello";

let s2 = "world!";

let ann = 42; // Any Display type

let result = longest_with_announcement(s1, s2, ann);

println!("Longest: {}", result);

}This combines generics and lifetimes seamlessly.

Common Pitfalls in Function Lifetimes

- Mismatched Lifetimes: If you return a ref without tying it to an input, it might imply ‘static, but that’s often wrong.

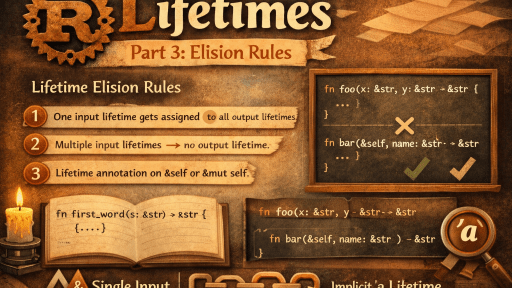

- Unnecessary Annotations: Rust has elision rules (covered in Part 3) that infer lifetimes in simple cases.

- Borrow Checker Errors: Messages like “does not live long enough” usually mean adjusting annotations or scopes.

Experiment with these in the Rust playground to see errors firsthand.

Lifetimes in Structs and Enums

Structs and enums can hold references, but to ensure safety, you must annotate their lifetimes. This ties the struct’s validity to the referenced data’s lifetime.

Defining Structs with Lifetimes

A struct holding references needs a lifetime parameter for each ref field (or shared if they relate).

Example: A struct for excerpts from a text:

struct Excerpt<'a> {

part: &'a str,

}

fn main() {

let novel = String::from("Call me Ishmael. Some years ago...");

let first_sentence = novel.split('.').next().expect("Could not find a '.'");

let ex = Excerpt { part: first_sentence };

println!("Excerpt: {}", ex.part);

}Here, Excerpt<‘a> means part lives at least as long as ‘a, and the instance ex can’t outlive novel.

If you try to use ex after novel drops, it won’t compile.

For multiple fields:

struct Book<'a, 'b> {

title: &'a str,

author: &'b str,

}But if they share the same lifetime source, use one ‘a:

struct Book<'a> {

title: &'a str,

author: &'a str,

}Enums with Lifetimes

Enums follow similar rules. They’re useful for variants with refs.

enum Highlight<'a> {

None,

Text(&'a str),

Code(&'a str),

}

fn main() {

let text = "Rust is awesome!";

let hl = Highlight::Text(text);

match hl {

Highlight::Text(s) => println!("Highlighted: {}", s),

_ => (),

}

}The ‘a ensures the enum doesn’t hold dangling refs.

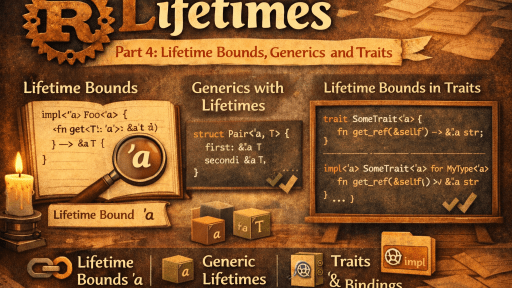

Impl Blocks and Methods with Lifetimes

When implementing methods on structs with lifetimes, carry over the parameters:

impl<'a> Excerpt<'a> {

fn announce_and_return_part(&self, announcement: &str) -> &str {

println!("Attention: {}", announcement);

self.part

}

}Note: The return is &str, but implicitly &’a str due to elision (more in Part 3). &self ties to ‘a.

This allows safe method chaining without lifetime issues.

Pitfalls in Structs and Enums

- Self-Referential Structs: Tricky; often require Pin or other advanced features (beyond basics).

- Lifetime Variance: Subtleties like covariance (we’ll touch on in advanced parts).

- Over-Annotation: Use elision where possible to keep code clean.

These concepts empower you to create data structures that borrow efficiently, like parsers or views into data without copying.

Stay tuned for Part 3, where we’ll explore lifetime elision rules and the special ‘static lifetime, with more examples and tips.