Welcome back to our deep dive into Rust lifetimes! In Part 1, we introduced the concept, explained why lifetimes are essential, and covered the basic syntax. Part 2 explored how rust lifetimes work in functions, structs, and enums, with practical code examples to illustrate their use.

In Part 3, we’ll demystify two key aspects that make working with lifetimes more intuitive: Lifetime Elision Rules, which allow you to omit annotations in common cases, and The ‘static Lifetime, which deals with references that live for the entire program’s duration. These topics will help you write cleaner, more idiomatic Rust code while still leveraging the borrow checker’s safety guarantees. As always, we’ll include detailed explanations and code snippets to solidify your understanding.

If you’re following along, try running these examples in your own Rust environment or the online playground to experiment.

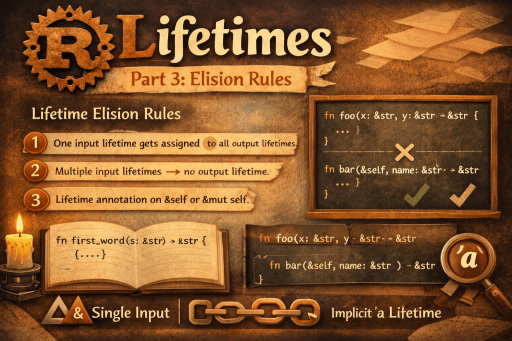

Lifetime Elision Rules: When You Can Skip Annotations

Explicit lifetime annotations can make code verbose, especially in simple scenarios. To address this, Rust provides lifetime elision rules—a set of heuristics that let the compiler infer lifetimes automatically. These rules apply to function signatures (and a few other places), allowing you to skip the <‘a> and ‘a markers when they’re obvious.

Elision doesn’t mean lifetimes are ignored; the borrow checker still enforces them. It just reduces boilerplate. If the rules don’t apply or lead to ambiguity, you’ll need to add explicit annotations.

The Three Elision Rules

Rust’s elision rules are straightforward and cover most common cases:

1. Each Input Reference Gets Its Own Lifetime: If there are no explicit lifetimes, each parameter that’s a reference (&T) is assigned a unique inferred lifetime. For example:

fn print_str(s: &str) { // Inferred as fn print_str<'a>(s: &'a str)

println!("{}", s);

}Here, s gets an implicit ‘a.

2.If There’s Exactly One Input Lifetime, It Applies to the Output: If the function has exactly one input reference (after rule 1), and the output is a reference, the output inherits that input’s lifetime.

fn first_word(s: &str) -> &str { // Inferred as fn first_word<'a>(s: &'a str) -> &'a str

let bytes = s.as_bytes();

for (i, &item) in bytes.iter().enumerate() {

if item == b' ' {

return &s[0..i];

}

}

&s[..]

}The return slice borrows from s, so it shares its lifetime.

3.Methods with &self or &mut self Inherit from self: In impl blocks, if the method has &self or &mut self, any output references without explicit lifetimes inherit self’s lifetime. This also applies if rule 2 would.

struct Excerpt<'a> {

part: &'a str,

}

impl<'a> Excerpt<'a> {

fn get_part(&self) -> &str { // Inferred as -> &'a str

self.part

}

}Since &self has ‘a, the return does too.

When Elision Doesn’t Apply

Elision only works for functions and methods. It doesn’t apply to structs, traits, or more complex cases like:

- Functions with multiple input references where the output needs to tie to a specific one (e.g., the longest example requires explicit ‘a because there are two inputs).

- Generic lifetimes mixed in unpredictable ways.

- When the compiler can’t unambiguously infer (it’ll error and suggest adding annotations).

Example where elision fails:

// This won't compile without explicit lifetimes

fn longest(x: &str, y: &str) -> &str {

if x.len() > y.len() {

x

} else {

y

}

}Error: “expected lifetime parameter”. Why? Two inputs, so rule 2 doesn’t apply (it requires exactly one). You need <‘a> as in Part 1.

Tips for Using Elision

- Start without annotations; add them if the compiler complains.

- Elision promotes readability but learn the rules to predict when it’s safe.

- In libraries, explicit lifetimes can make APIs clearer for users.

Mastering elision will make your code feel more like higher-level languages while keeping Rust’s safety.

The ‘static Lifetime: Eternal References

The ‘static lifetime is special—it’s built-in and denotes references that are valid for the entire lifetime of the program. Think of it as “eternal” or “global” references. They’re useful for constants, string literals, and data that doesn’t depend on runtime scopes.

When to Use ‘static

‘static applies to:

- String literals: “hello” has type &’static str.

- Constants: const or static declarations.

- Data embedded in the binary, like leaked boxes (though leaking is advanced).

Example:

fn static_example() -> &'static str {

"This string lives forever!"

}This is safe because the string is a literal, baked into the executable.

In generics or bounds:

fn print_static<T: std::fmt::Display + 'static>(item: &T) {

println!("{}", item);

}The + ‘static bound requires T to contain no non-‘static references. This is common in threads, where data must outlive the main program.

‘static in Structs and Functions

You can use ‘static in structs for holding global data:

struct GlobalConfig {

name: &'static str,

}

const APP_NAME: &'static str = "RustApp";

fn main() {

let config = GlobalConfig { name: APP_NAME };

println!("App: {}", config.name);

}For functions returning ‘static:

fn get_version() -> &'static str {

env!("CARGO_PKG_VERSION") // Macro expands to a 'static str

}Common Misuses and Pitfalls

- Not Everything is ‘static: Don’t force ‘static on short-lived data; it can lead to unnecessary cloning or leaking.

- Thread Safety: ‘static is often required for std::thread::spawn because threads can outlive the main scope.

fn main() {

let data = "Not 'static".to_string(); // Lives only in main

// std::thread::spawn(|| println!("{}", data)); // Error: data not 'static

let data_static: &'static str = "Now it is";

std::thread::spawn(|| println!("{}", data_static)); // OK

}- Leak for ‘static: Use Box::leak to create ‘static from owned data, but sparingly—it’s like manual memory management.

fn leak_to_static(s: String) -> &'static str {

Box::leak(s.into_boxed_str())

}Understanding ‘static helps with APIs involving globals, configs, or long-lived data.

These tools—elision for simplicity and ‘static for permanence—round out the core of lifetime management.

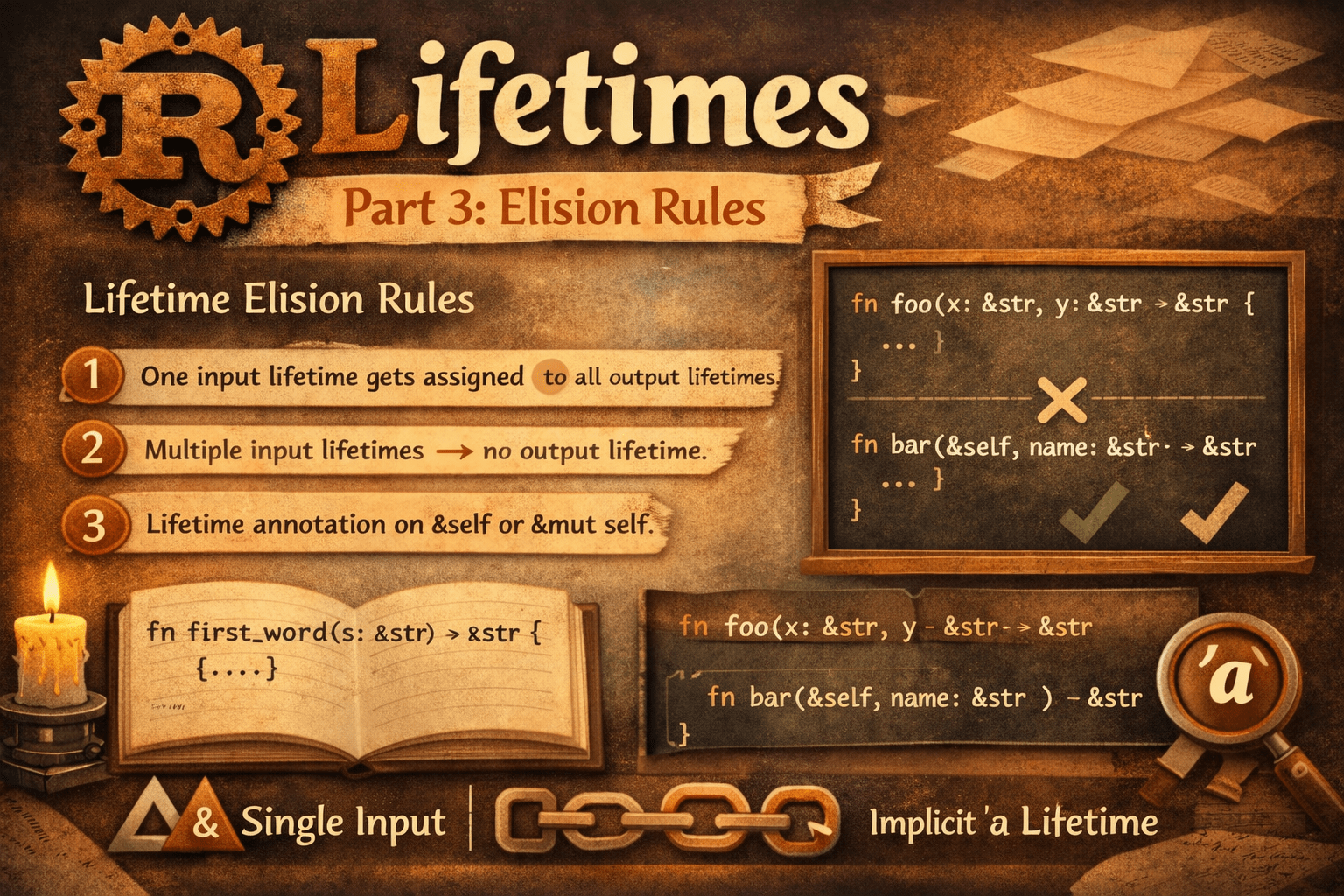

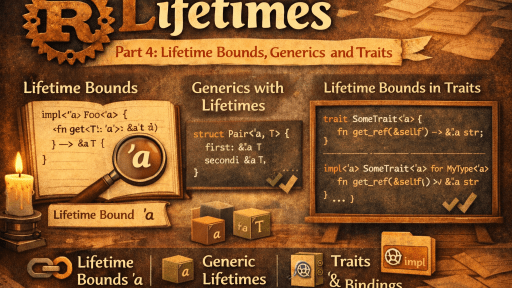

Join us in Part 4 for advanced topics like lifetime bounds, generics integration, traits, and troubleshooting common errors. We’ll include more complex examples to challenge your skills.