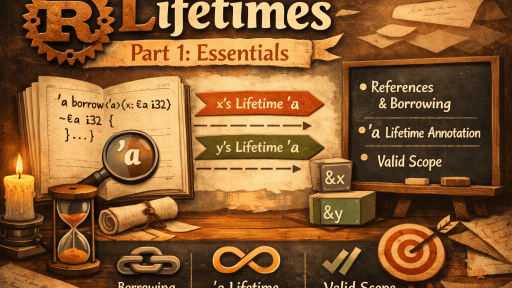

Welcome back, rustaceans! We’ve come a long way in our exploration of Rust lifetimes. In Part 1, we laid the groundwork with introductions and basics. Part 2 applied lifetimes to functions, structs, and enums. Part 3 simplified things with elision rules and introduced the enduring ‘static lifetime.

Now, in Part 4, we’re leveling up to advanced territory. We’ll tackle Advanced Topics: Lifetime Bounds, Generics, and Traits, where lifetimes integrate with Rust’s powerful type system for even more flexible code. Then, we’ll address Common Lifetime Errors and How to Fix Them, equipping you with debugging strategies for those pesky borrow checker complaints. As always, expect in-depth explanations, code examples, and practical tips to make these concepts stick.

If you’re coding along, remember: the borrow checker is your friend—it catches issues early. Let’s dive deeper!

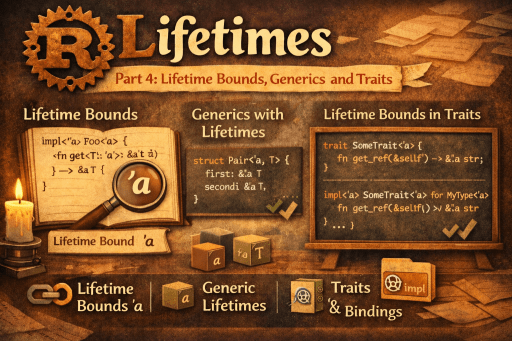

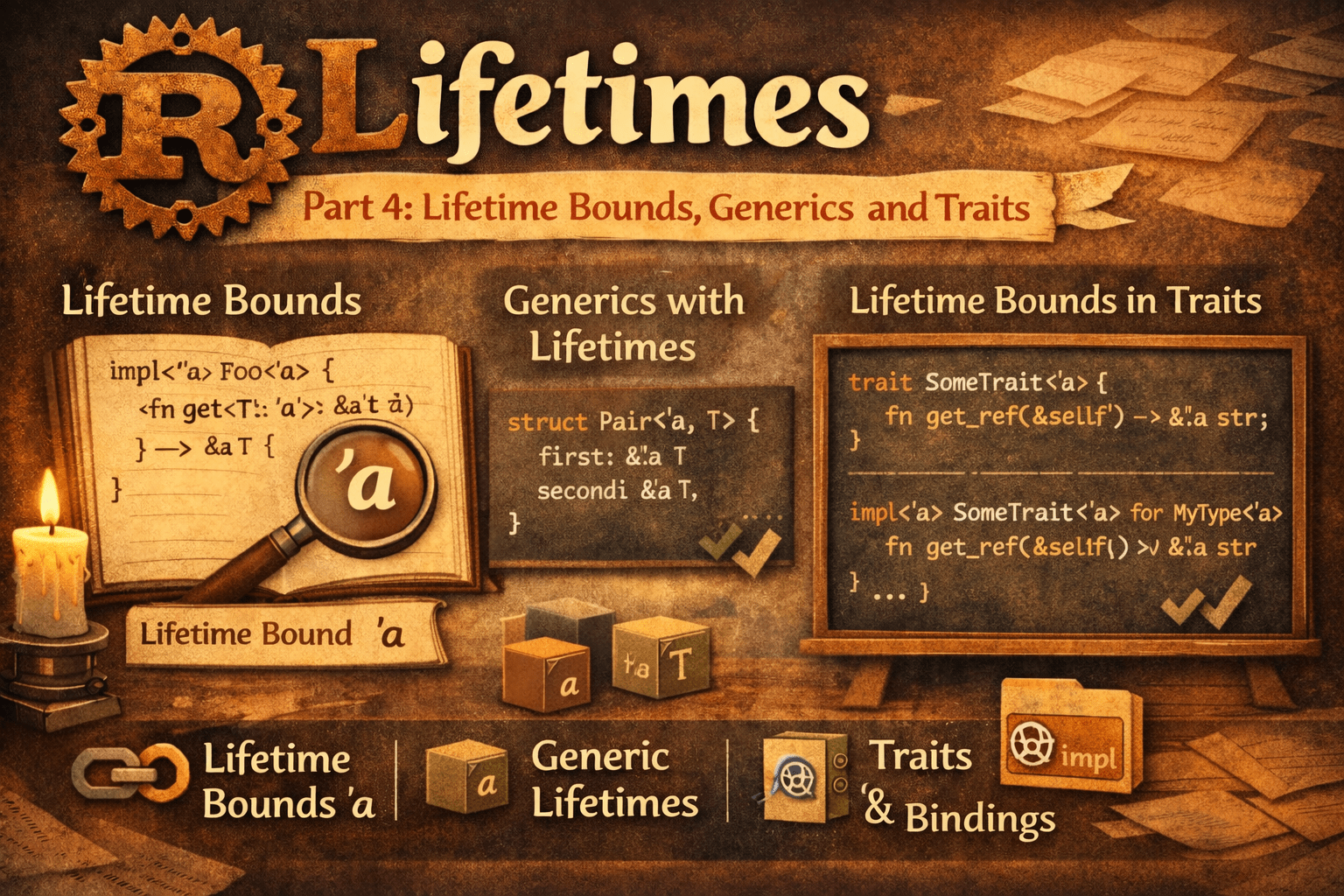

Advanced Topics: Lifetime Bounds, Generics, and Traits

Once you’re comfortable with basic lifetimes, you’ll encounter scenarios where they intersect with generics and traits. This is where Rust’s type safety really shines, allowing you to write abstract, reusable code without sacrificing memory guarantees.

Lifetime Bounds

Lifetime bounds constrain how long a reference must live, similar to trait bounds for types. They’re specified using + ‘a syntax in generics or where clauses.

For example, a trait bound with a lifetime:

fn process_data<T>(data: T)

where

T: std::fmt::Display + 'static,

{

println!("{}", data);

}Here, T must implement Display and have a ‘static lifetime (no borrowed data shorter than ‘static).

More commonly, bounds relate lifetimes:

struct RefWrapper<'a, T: 'a> {

ref_field: &'a T,

}The T: ‘a bound means T must outlive ‘a. This is useful when T itself might contain references.

In functions:

fn longest_with_bound<'a, 'b: 'a>(x: &'a str, y: &'b str) -> &'a str {

if x.len() > y.len() {

x

} else {

y // Safe because 'b outlives 'a

}

}The ‘b: ‘a says ‘b outlives ‘a (written as ‘b > ‘a in some docs, but syntax is ‘b: ‘a). This allows returning y with ‘a lifetime, as the compiler knows ‘b is at least as long as ‘a.

Bounds prevent invalid lifetime relationships at compile time.

Integrating Lifetimes with Generics

Generics (<T>) and lifetimes (<‘a>) often go hand-in-hand for polymorphic code.

Consider a generic struct with references:

struct Pair<'a, T> {

first: &'a T,

second: &'a T,

}

fn create_pair<'a, T>(a: &'a T, b: &'a T) -> Pair<'a, T> {

Pair { first: a, second: b }

}Here, T is generic, but both refs share ‘a.

For more flexibility, multiple lifetimes and generics:

fn compare<'a, 'b, T, U>(x: &'a T, y: &'b U) -> bool

where

T: PartialEq<U>,

{

x == y

}This requires T to be comparable to U, ignoring lifetimes for the comparison but enforcing them for borrowing.

Generics + lifetimes enable libraries like iterators or parsers that borrow efficiently.

Lifetimes in Traits

Traits can declare lifetime parameters, especially when dealing with references.

Defining a trait with lifetimes:

trait Parser<'a> {

fn parse(&self, input: &'a str) -> &'a str;

}Implementing it:

struct JsonParser;

impl<'a> Parser<'a> for JsonParser {

fn parse(&self, input: &'a str) -> &'a str {

// Simplified: return the input as-is

input

}

}The ‘a in the trait ties the input and output lifetimes.

For trait objects, lifetimes are crucial:

fn get_parser<'a>() -> Box<dyn Parser<'a> + 'a> {

Box::new(JsonParser)

}The + ‘a bounds the trait object’s lifetime.

In associated types or methods, lifetimes ensure safety across implementations.

These integrations allow for abstract interfaces that respect borrowing rules, like in web frameworks or data processing pipelines.

Advanced Tips

- Variance: Lifetimes have covariance (e.g., &’static T can be treated as &’a T for any ‘a). Understand subtyping for complex cases.

- Higher-Rank Trait Bounds (HRTBs): For closures, use for<‘a> syntax, like Fn(&’a str) -> &’a str. This is advanced but powerful for functional programming.

- Performance: Lifetimes enable zero-copy operations, boosting efficiency in hot paths.

Practice with crates like serde or tokio to see these in action.

Common Lifetime Errors and How to Fix Them

Even seasoned Rust developers wrestle with lifetime errors. The good news? They’re descriptive, and fixing them builds intuition.

Error: “Does Not Live Long Enough”

This means a reference is used beyond its valid scope.

Example:

fn main() {

let r;

{

let x = String::from("hello");

r = longest(&x, "world"); // Assume longest from earlier

}

println!("{}", r); // Error: x dropped, but r uses it

}Fix: Ensure the referenced data outlives the reference. Move x out of the inner scope or clone if needed.

Error: “Expected Lifetime Parameter”

Happens when elision can’t infer, like multiple input refs.

Fix: Add explicit <‘a> and annotate as in longest.

Error: “Cannot Infer an Appropriate Lifetime”

Ambiguous relationships in generics or closures.

Example with closure:

fn returns_closure() -> impl Fn(&str) -> &str {

|s| s

}Error: Needs HRTB impl for<‘a> Fn(&’a str) -> &’a str.

Fix: Use for<‘a> to quantify over lifetimes.

Error: “Borrowed Value Does Not Live Long Enough” in Loops

Common in loops creating temp values.

Fix: Use owned types or adjust scopes.

General Debugging Strategies

- Read the error spans: They point to borrow and drop sites.

- Add explicit annotations temporarily to isolate issues.

- Use rustc –explain E0507 for detailed docs on error codes.

- Refactor: Sometimes, owning data instead of borrowing simplifies.

- Tools: Clippy lint cargo clippy catches subtle lifetime misuse.

With practice, these errors become rare, and your code more robust.

We’ve covered the advanced and troubleshooting sides—essential for mastering lifetimes.

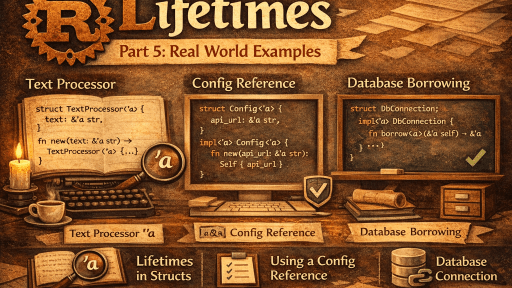

Look forward to Part 5, the finale with real-world examples, best practices, conclusion, and resources. It’ll tie everything together with actionable insights.